Picture this: You’ve solved a tricky problem and someone asks, “How did you figure that out?” You launch into an explanation, eager to share your process. But as you speak, you find yourself jumping between ideas, backtracking to add forgotten details, and watching confusion grow on their face. What made perfect sense in your head is coming out as a jumbled mess. Midway through, you realize your explanation isn’t wrong, but it’s certainly not helpful either.

This was my reality for years. Early in my career, I operated purely on intuition. I was given the autonomy and safety needed to approach complex problems in my own way, so I’d follow my gut. I couldn’t articulate my approach beforehand, and even after sitting with a challenge long enough for the path to become clear to me, I still struggled to express that understanding to others.

My colleagues appreciated how I could wade through complex situations with multiple variables and bring clarity to the mess. But when they asked how I did it, my attempts to explain would quickly unravel into that same jumbled chaos.

This lack of articulation created a paradoxical situation: I was confident in my abilities to solve problems, but completely insecure in my ability to explain what felt so natural in my mind. As I advanced in my career, this limitation became a serious obstacle. People wanted to learn from me, but I couldn’t teach what I couldn’t explain.

My inability to articulate my process created real consequences. I couldn’t give pointed feedback to colleagues because I couldn’t explain why something wasn’t right or how to improve it. I’d recognize when something needed adjustment, but without the language to guide others, I remained silent, hoping things would work out.

In these moments, I felt like a fraud—not because my work wasn’t good, but because I couldn’t explain my ideas. The irony was crushing: I avoided sharing thoughts not because I doubted their value, but because I feared I couldn’t express them clearly enough for others to grasp their necessary complexity.

This revealed an important aspect of the confidence gap that often goes unrecognized: sometimes it’s not about doubting our ideas at all; it’s about doubting our ability to communicate them effectively. Discussions of confidence often focus on self-doubt about the quality of our thinking, but my experience highlights a different and particularly frustrating dimension—being certain your ideas have value, but being unable to express them clearly enough to work with others on them. There’s a special kind of anguish in knowing you have something good to contribute but feeling trapped by your inability to articulate it in a way others can understand.

Behind this communication challenge lies a deeper issue—vulnerability. When I share an idea, I’m sharing a part of myself, an expression of who I am at that moment. This creates an inherent risk: if I believe I’m right, share my idea confidently, and then discover I’m wrong … what does that say about me?

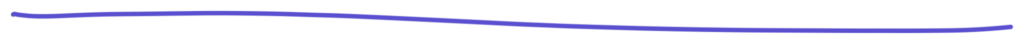

This vulnerability creates a loop: fear of inadequate expression leads to withholding ideas, which prevents practice, feedback, and refinement, which reinforces the fear. Breaking this cycle requires both tools and techniques for expression and a shift in how we frame the purpose of our contributions.

Breaking the Cycle: From Invisible to Visible

My breakthrough came when I applied to speak at a conference about my process for “Modeling for Clarity.” Facing a deadline, I was forced to make my implicit knowledge explicit—essentially applying to my own thinking the very process I had been using intuitively all along.

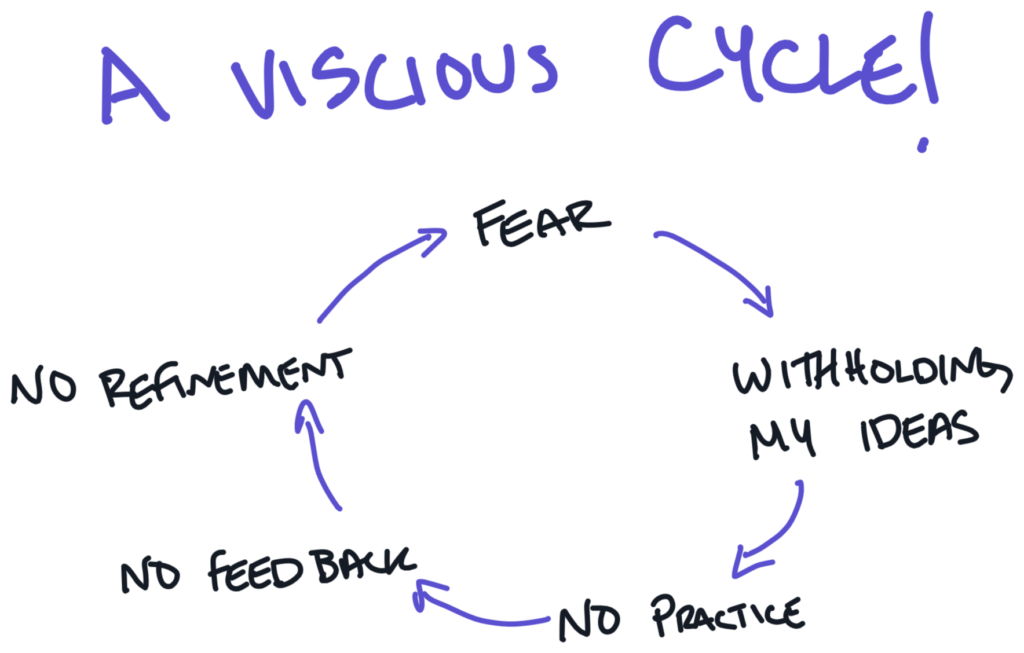

The key insight was realizing that we need to get ideas out of our heads before we can truly see what we have. Once externalized, we can begin the analytical process of understanding what we have and how each piece relates.

The most powerful tool I discovered was visualization—not artistic rendering, but simply making invisible thoughts visible. We often forget how much easier it is for humans to understand visuals than language alone.

Something transformative happens when we put an idea on paper. Even something as simple as writing a word and putting a box around it turns an abstract concept into a tangible object that can be referenced, pointed to, and described.

This visualization offers dual benefits:

- For individual thinking: It offloads working memory, allowing me to reference ideas spatially rather than trying to hold everything in my head. I can remember that the thing I want is “over there” and “looks like that”, rather than remembering the thing I want is called “newsletter”.

- For collaborative thinking: It ensures shared understanding. When I say “newsletter,” you might imagine something completely different. When I can point to a box labeled “newsletter,” drawing your attention to the visual, we know we’re discussing the same concept.

As Nick Sousanis writes in Unflattening:

“Drawing is a means of orchestrating a conversation with yourself. Putting thoughts down allows us to step outside ourselves and tap into our visual system and our ability to see in relation… We draw not to transcribe ideas from our heads but to generate them in search of greater understanding.”

The beauty of this approach is its simplicity and accessibility. You don’t need to be an artist or have special training. You just need to start with one object, one thing:

1. Gather simple tools: A piece of paper and a pen, or a whiteboard and marker. The less fancy the better; there’s something about the hand-mind connection that digital tools can’t quite replicate.

2. Build incrementally: Add more objects as placeholders for your thoughts, one at a time, each on its own sticky note or boxed-in word. Keep adding until it gets hard to think of more.

3. Map relationships: Draw arrows between related elements; label the arrows if you can. Don’t worry if you can’t label every connection perfectly—recognizing a relationship exists is the first step to defining it. Going deeper: Not all relationships want to be expressed with boxes and arrows, try nested boxes to show “this is inside of this” relationships.

4. Create a single visual object: Write a word that represents one aspect of your idea and put a box around it. Don’t worry about getting everything out at once. Creating that first visual anchor will help you think of the next element.

5. Look for patterns: As your collection grows, stand back and observe.

– What groupings emerge?

– Does seeing what’s there highlight what isn’t?

– Are there objects that don’t seem to fit into the whole? Do you know why?

– Do you need to remove that one or find more like it?

The process mirrors exactly what happens intuitively when we are forced to venture into the unknown: we start with what we know, add what we discover, and gradually build a mental map that makes the unfamiliar navigable. Here, we’re just extending that process into the world we can see.

When I finally followed this process to prepare for my presentation, I hadn’t gathered anything new from external sources. I had arranged what I already knew into a structured format that allowed me to learn more about what I thought I already knew in my head.

This was the crucial shift: I gained confidence not because my ideas changed, but because I could now see them, share them, and build on them with others. I could engage in conversations with a newfound confidence in the structured version of my ideas; conversations I previously would have avoided out of fear of not being able to express my tangled web of ideas.

Starting Is Better Than Getting It Right

The most important insight from my journey is that we don’t have to get all parts of an idea out of our heads at once. In fact, we can’t. When I try to hold an entire complex idea in my mind while focusing on articulating one part, I often lose track of the whole—it vanishes from my mind’s eye.

Instead, I’ve learned to trust that starting with one element—whatever is top of mind—will lead to the next, and the next. The thinking-and-seeing loop becomes self-generating, with each externalized element sparking connections to others.

This is why starting is better than getting it right. If we wait until we’ve figured it all out in our heads, we’ll likely never share our ideas. The perfect mental model will remain trapped where only we can access it.

I still face this challenge regularly. Even now, I have ideas that feel crystal clear in my head but would come out as a jumbled mess if I tried to explain them without first doing this visualization work. The difference is that now I recognize the gap and know what to do about it. I’ve stopped expecting clarity to emerge magically from my speech. Instead, when something matters, I externalize my ideas, either beforehand or in real time as I am explaining.

And that’s the key: knowing how to make ideas clear doesn’t automatically make all ideas clear. It still takes deliberate effort each time. For every model I’ve created and shared publicly, there are dozens more in my notebooks where I worked through the mess to find clarity. The work doesn’t disappear; you just get better at knowing when and how to do it.

Look at the ideas currently trapped in your head. What’s stopping you from expressing them? Is it fear they won’t be understood? Worry they’re not fully formed? Concern about how they’ll be received?

Whatever the barrier, remember that great ideas rarely emerge fully formed. They develop through the process of expression and iteration. The simple act of making your thoughts visible—to yourself first, then to others—is often all it takes to begin bridging the confidence gap.

Grab a pen and paper right now. Write one word that represents an idea you’ve been holding onto, put a box around it, and start the conversation with yourself. That single step might be all it takes to set your best ideas free.