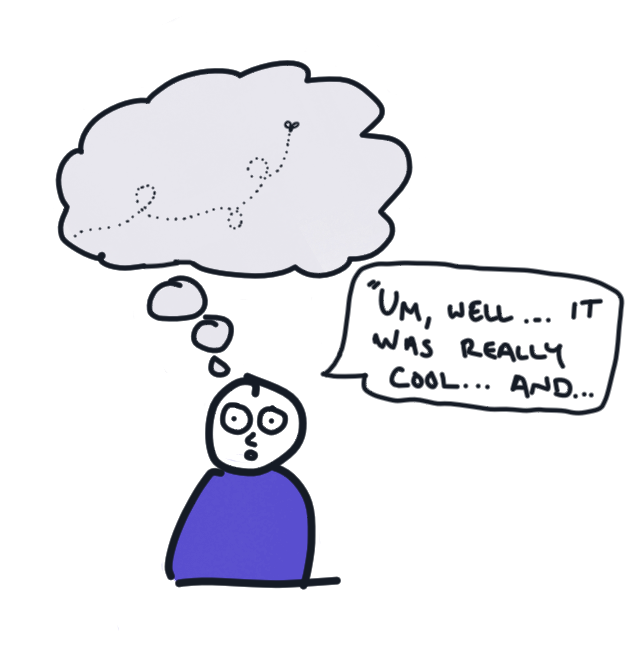

Have you ever left a meeting feeling aligned with everyone, only to discover later that you can’t reconstruct what you heard? The clarity that felt so palpable in the moment somehow evaporates when you try to explain it to someone else or apply it yourself.

I am not talking about mindlessly nodding along; I’m talking about when you genuinely are tracking with someone’s thinking in real-time, yet finding yourself unable to reconstruct that same coherence later. I find this phenomenon maddening and it extends beyond meetings; I have noticed it whenever information is being conveyed verbally—like hearing a great podcast or TED talk, only to find the clarity dissolving as you attempt to relay it to a friend.

Rivers & Lakes, Chains & Webs: The Transformation of Understanding

Information can be understood through two complementary metaphor systems: how we experience it (rivers vs. lakes) and how it’s structured (chains vs. webs).

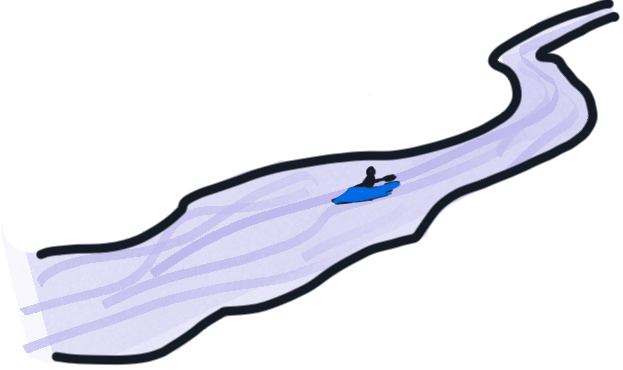

Verbal information is encountered like a flowing river. Each idea rushes past, quickly replaced by the next, in a sequence we can’t control. As listeners, we make split-second decisions about what to focus on and how to keep track of what we hear, never knowing which elements will prove most valuable later.

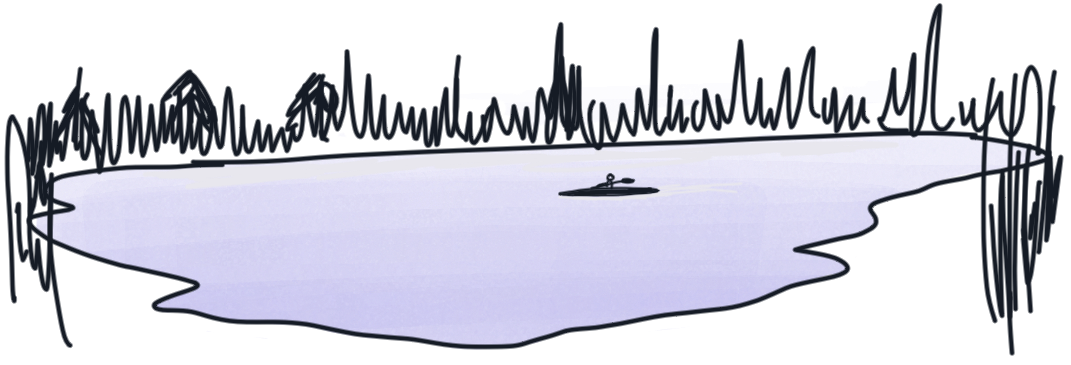

Visual information, by contrast, is more like encountering a still lake. All ideas and elements remain simultaneously visible, allowing us to survey the whole before deciding where to focus. Nothing disappears as we examine one area—the entire surface remains accessible and we can dive down when needed.

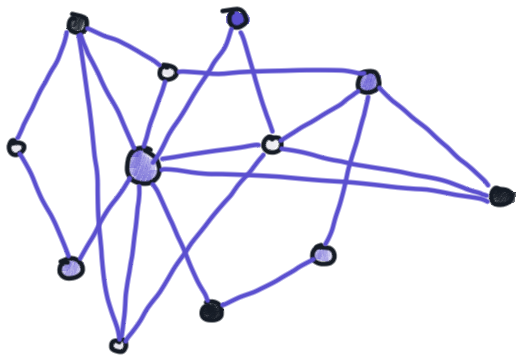

This experience of information is directly tied to its structure. In our minds, ideas exist as a complex web of interconnected concepts. When we convey those ideas verbally, we must flatten this web into a linear chain—a one-dimensional path through a multidimensional understanding. The result isn’t necessarily bad, but it is fundamentally limited; two deeply related ideas might be mentioned several minutes apart because the chosen path through the web of ideas determined which connections would be made explicit and which would remain implied.

Rivers flowing into Lakes, Chains woven into Webs

Hand-written note-taking begins a dual transformation. While verbal information flows like rivers and unfolds in chains, visual note-taking creates still lakes where ideas are arranged in webs. This practice isn’t merely a recording technique—it’s visual thinking made tangible, a fundamentally different way of processing and preserving understanding.

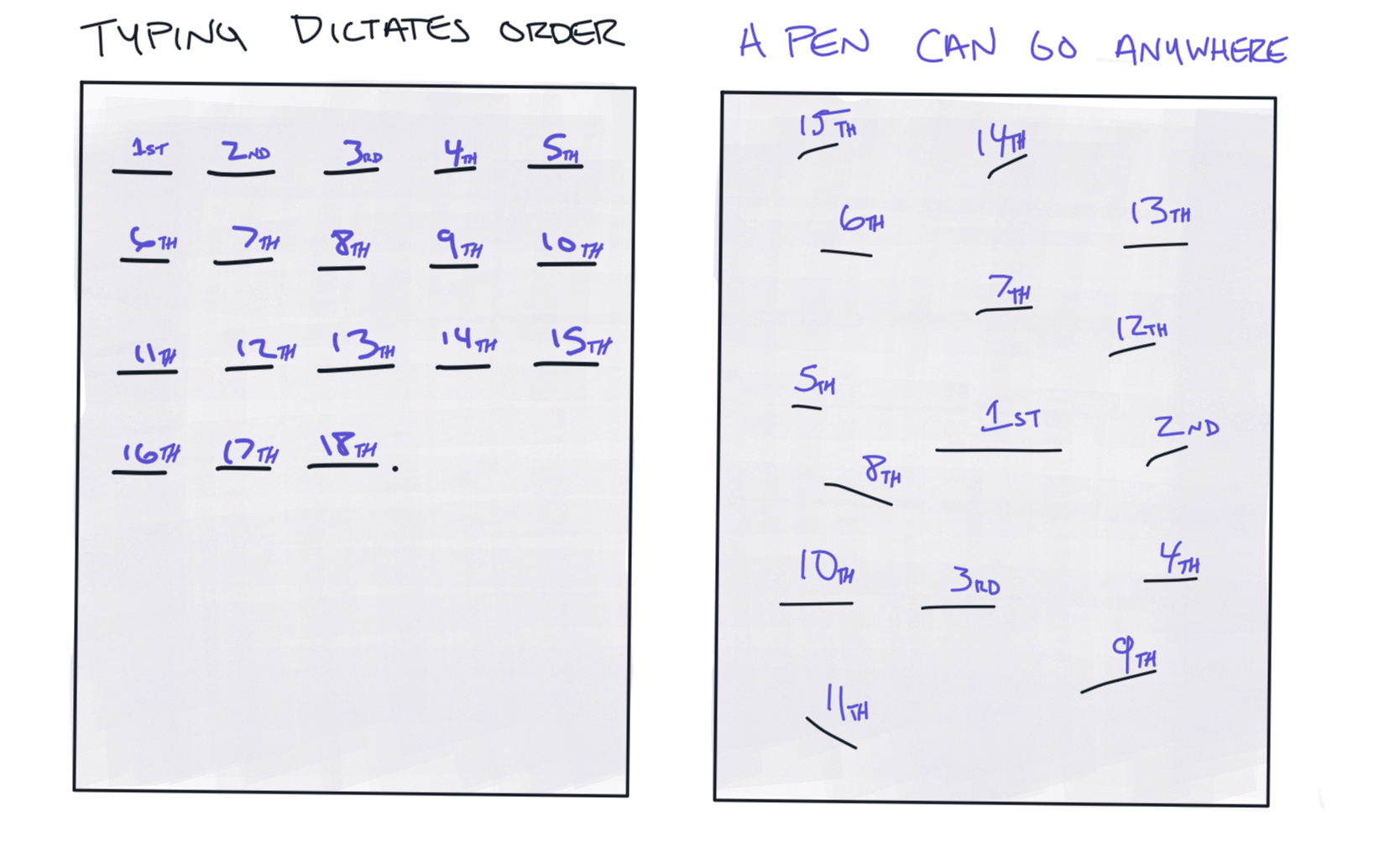

Where verbatim transcription merely recreates a river, handwriting does two things: 1) forces real-time synthesis & 2) unlocks a second dimension. The relative slowness of handwriting forces selectivity and synthesis; anything that makes it on the page needs to be connected with something in my brain and have some meaning. While this is a limitation, it also means that everything in front of me is ready to be related to the next thing I hear.

Additionally, by having the two-dimensional freedom a physical canvas offers (over the single dimension of a string of words), I can begin creating relationships that are implied by what was said, but that wasn’t literally what was said. As the river’s flow is captured in the stillness of a lake, the sequential chain of spoken ideas transforms into a web of relationships. The physical artifacts we create train our minds to perceive connections and structures that verbal processing often misses.

The result is a meaning-laden set of notes that can use spatial (relative position-based), symbolic (image-based), and linguistic (word-based) expressions of meaning. We can step back to see the whole, zoom in on details, or draw new connections between elements that were far apart in the original telling. The linear constraints of time dissolve, and what emerges isn’t just better documentation—it’s a visible manifestation of a richer cognitive landscape where ideas exist in their naturally interconnected state.

The Triple Power of Visual Artifacts

The transformation from verbal rivers to visual lakes—from linear chains to interconnected webs—offers three distinct but complementary advantages:

1. Enhanced Real-Time Understanding

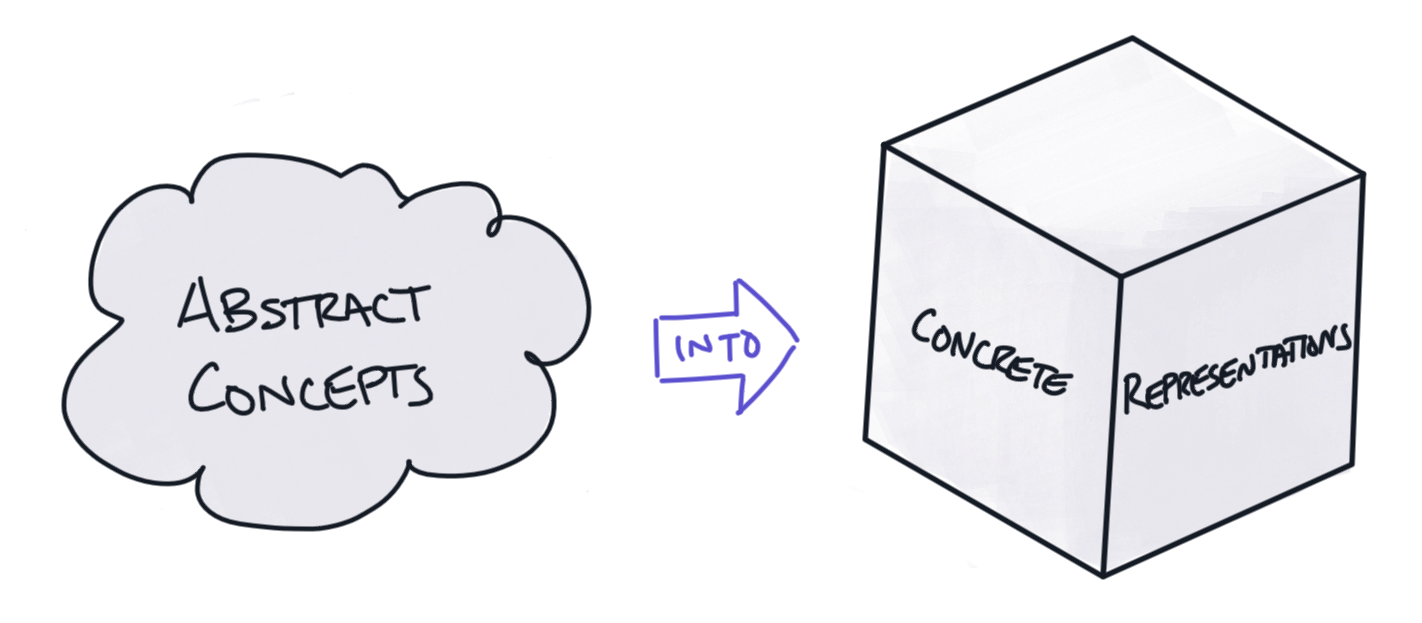

When we create visual artifacts during a conversation, we don’t just record information—we process it. Selecting what to capture and how to arrange it forces us to engage with ideas at a deeper level than passive listening. This synthesis transforms abstract concepts into concrete representations that reflect our actual understanding, not just what was said.

2. Revealed Relationships Between Ideas

Visual notes excel at something verbal communication inherently struggles with: showing multiple relationships simultaneously. On the page, we can explicitly show connections between concepts mentioned far apart in time, group related ideas spatially, and use visual hierarchies to indicate importance. These relationships—often implied but never stated in the original telling—become explicit in our visual web.

3. Persistent Access to Complex Understanding

Perhaps the most powerful benefit emerges long after the notes are created. Unlike verbal information which fades like a river flowing past, visual artifacts remain stable. A single glance at notes from weeks ago can reactivate entire networks of understanding. We can enter at any point, explore in any direction, and add new connections as our understanding evolves—all without needing to reconstruct the entire sequence of the original conversation.

Simple Techniques for River-to-Lake Transformation

Creating effective visual notes doesn’t require artistic talent or specialized training, but it does take practice. The goal isn’t perfection—even so-called “imperfect” visual notes provide real value—but rather making thinking visible in ways that reveal rich relationships between ideas. As you develop your method of taking handwritten notes, here are three ways to transform chains back into webs:

1. Use Metaphor: Metaphors relate abstract concepts to concrete things creating hooks for our memory. As you hear something, does it remind you of something else? Use that as a way to remember what something means to you. (For example: instead of writing out how verbal information can get lost after you hear it, you could sketch a river or write “like a river” to associate meaning)

2. Use Space: Use the page’s two-dimensional space to group related concepts regardless of when they were heard. As you begin, keep room between the things you put on the paper, as you’re waiting to make connections on the page, the things you add to the page might be in sequential order, that’s a great way to start. Just don’t crowd them too much or you won’t be able to put related things near each other.

3. Use Connections: Add arrows or lines showing relationships between ideas that may have been separated by time in the original telling. This can help if you don’t have room to put related things near each other or if there is something specific to say (expressed via a label on the connective arrow).

The act of creating these visuals fundamentally changes how we process information. Instead of trying to memorize a river of chained ideas, we actively collect ideas in a lake of webbed relationships that we can come back to later. By transforming the chain of information into a web of relationships we strengthen our memory and deepen our understanding.

Reclaiming the Web of Understanding

Conversations disappear like rivers flowing past—a chained sequence of moments swept away by time. But when we create visual artifacts, we perform a profound transformation: we reclaim the web of interconnected ideas that was flattened into a chain of words.

This isn’t simply about better notes—it’s about reconstructing the true relationships between ideas that sequential presentation inevitably obscures. Instead of being passive recipients in a river of information, we become active reconstructors of knowledge lakes where ideas exist in their natural, interconnected state.

By developing a practice of visual thinking, we liberate ideas from the sequential presentation that verbal communication requires. We transform rivers into lakes and chains into webs, creating artifacts that allow us to approach complex ideas from multiple angles, discovering insights and relationships impossible to perceive in the original linear format. In a world of endless verbal inputs, these visual landscapes become sanctuaries where understanding can develop and deepen over time.